Every American who grew up in the mid-20th century or later knows that special smell of a newly opened can of Play-Doh, the smell of a virgin cylinder of colourful dough with endless possibilities ahead.

Hasbro, the US-based toy giant that owns the Play-Doh brand, has applied to register that smell with the USPTO. Application number 87335817, filed in March, 2017, is titled “NON-VISUAL PLAY-DOH SCENT MARK”. The mark description in the application is “a scent of a sweet, slightly musky, vanilla fragrance, with slight overtones of cherry, combined with the smell of a salted, wheat-based dough”.

But we all know it as, simply, the smell of Play-Doh.

A use-based application in the US must provide a specimen of use of the mark in commerce, so Hasbro submitted a can of Play-Doh for the examiner to sniff.

The examiner issued an office action in May 2017, refusing registration. First, he said that the smell was a non-distinctive feature; that lots of toy moulding compounds have scent, and that the purpose of the scent was to make the goods appealing, not as an indicator of source. Under the doctrine of aesthetic functionality, a feature is functional because it makes the product more desirable.

The second ground for refusal was that Hasbro had not provided enough evidence that the mark had become distinctive, because an aspect of a product design, as opposed to packaging, must have demonstrated acquired distinctiveness (“secondary meaning”) before it can be registered or protected as a mark.

Hasbro responded with arguments and reams of evidence of the distinctiveness of the smell mark, including, for example a STOP AND SMELL THE PLAY-DOH advertising campaign, and articles referring to the “beloved, nostalgic, and readily-identifiable PLAY-DOH scent”.

The examiner has not yet reacted to this submission.

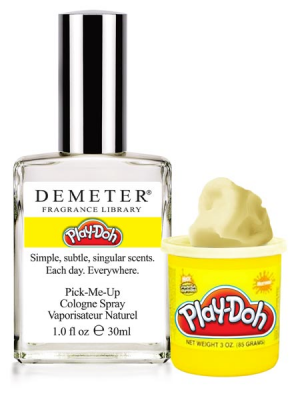

The Play-Doh smell is so well known that a US perfume company issued a Play-Doh fragrance. The ad copy reads: “When you open a can of PLAY-DOH compound, you are instantly transported back to childhood. What better way to celebrate the 50th birthday than by bottling the scent for adults everywhere to enjoy as a reminder of their youth.”

This is not the only smell mark applied for in the USA, but there are very few marks where the applicant has convinced the Trademark Office that the smell is an indicator of source and not functional. For example, in 2015, a Brazilian company registered the “scent of bubble gum” for shoes, sandals and flip flops, and in 2016, Le Vain Corp, of the USA, registered the scent of chocolate for “retail store services featuring jewelry, diamond jewelry, gemstone jewelry, gems, watches, rings, earrings, bracelets, bangles, cufflinks, necklaces, pendants, jewelry pins and consumer goods; trade show services, namely, kiosks and display cases for the presentation and sale to others of jewelry, diamond jewelry, gemstone jewelry, gems, watches, rings, earrings, bracelets, bangles, cufflinks, necklaces, pendants, jewelry pins and consumer goods”.

Verizon, the cell-phone carrier, registered 4618936 in 2014 for the “flowery musk scent” used in its retail stores.

One difference between these marks and the Play-Doh mark is that one does not experience the smell until after the purchase, when the can is opened. One wonders if that will make a difference.

A European take

David Fyfield of the IP Emerging Issues Team provides the EU take on this: “Despite the popularity of Play-Doh in Europe, Hasbro would have an even trickier task to register its smell as a European Union trade mark. Although it is no longer necessary for signs to be capable of being represented graphically to qualify as an EUTM, the EUIPO is still of the view that there is no generally available technology that is capable of representing a smell with sufficient clarity and precision for it to be registerable.”

Janet Satterthwaite is a Partner at Potomac Law Group, Washington DC. David Fyfield is an Associate at Charles Russell Speechlys LLP in London.

Play-Doh photo by Nolan Williamson via Flickr

Issue 085

Issue 085

Issue 085

Issue 085